Europe’s Role in Ape Evolution Expanded by Fossil Discoveries

New fossil discoveries reshape understanding of ape evolution. Europe emerges as a key player in the great ape lineage.

Europe’s role in ape evolution expands with new fossil discoveries, revealing coexistence of two ancient great ape species outside Africa.

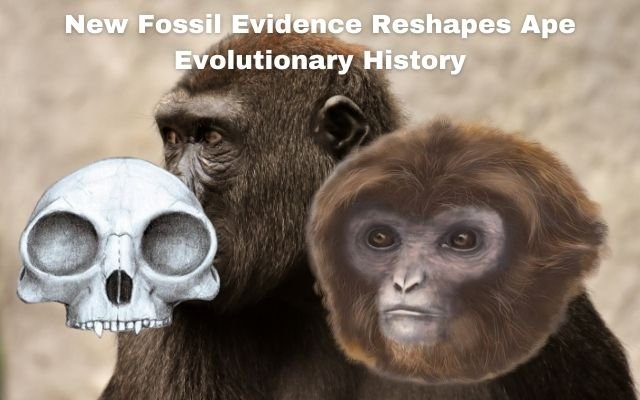

In a significant discovery, fossils found in a Bavarian clay pit suggest that two different species of ancient apes lived together in Europe millions of years ago. Among these was what might be smallest great ape ever found. This marks first time that researchers have identified different ape species coexisting outside of Africa, each with its own unique body structure and diet.

Previously, Hammerschmiede site in Germany revealed fossils of Danuvius guggenmosi, a 11.6-million-year-old extinct great ape. This species gained attention for being possibly oldest known upright walker, according to a team led by paleontologist Madelaine Böhme from Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen in Germany.

Madelaine Böhme and her team have recently reported discovery of three new fossils in same sediment layer where Danuvius fossils were previously found. These new fossils belong to a newly identified great ape species called Buronius manfredschmidi. Among fossils, team uncovered a partial upper molar and a kneecap found close together, which likely belonged to a young, sexually immature ape, according to Böhme. Additionally, partial lower premolar was found about 25 meters away, which is believed to have come from an adult ape. This finding was published on June 7 in journal PLOS One.

Size and shape of these fossils suggest that Buronius was very small great ape, weighing only about 10 kilograms. This would make it smallest known great ape ever discovered. For comparison- modern siamangs, type of gibbon classified as a lesser ape, also weigh around 10 kilograms.

Although only few fossils have been found, they provide important clues about Buronius’ lifestyle. Thin outer layer of tooth enamel indicates that Buronius likely had a diet consisting of soft foods. Fossil kneecap, which is relatively short and thick, suggests that Buronius was an excellent climber. This implies that ape probably spent much of its time in trees, eating leaves from high branches and enjoying sweet fruits during summer and fall seasons.

Danuvius was a much larger ape compared to Buronius, growing to about twice its size. It had strong teeth with thick enamel, which allowed it to eat tough foods like mollusks, nuts, roots, underground stems, and even small animals. This difference in diet suggests that Danuvius and Buronius occupied different ecological niches, allowing them to coexist in the same environment.

If the findings by Böhme and her team are accurate, the Hammerschmiede site in Germany is the first location outside of Africa where two different species of great apes lived side by side during the Miocene Epoch. The Miocene Epoch, which lasted from about 23 million to 5 million years ago, was a critical period in the evolution of great apes, a group that includes modern-day chimps, gorillas, orangutans, and humans.

The fact that these two apes, Danuvius and Buronius, could survive on different food sources in the same area suggests that the ecosystems in Europe during the Miocene encouraged the evolution of a diverse range of ape species. With the discovery of Buronius, the number of great ape genera found in Europe from about 16 million to 6 million years ago has risen to 16, which is more than twice the number found in Africa from the same period.

However, the discovery of only three fossils of Buronius leaves some uncertainty about its place in the evolutionary tree. There is still a question of whether Buronius is indeed a separate species or if the fossils might actually belong to juvenile Danuvius individuals.

For example: some features of the Buronius teeth resemble those of a group of ancient Eurasian apes called pliopithecoids, which have no living descendants. Paleoanthropologist Clément Zanolli from the University of Bordeaux in France suggests that further studies, especially imaging of the internal structure of the teeth, will help clarify where Buronius fits in the lineage of ancient European apes.

Debate continues among experts. Sergio Almécija, a paleoanthropologist from American Museum of Natural History in New York City, suggests that fossils might actually belong to young Danuvius individuals rather than separate species. He points out that kneecap found with fossils is as large as those of smaller adult orangutans, raising questions about its true identity. Similarly, paleoanthropologist Kelsey Pugh of Brooklyn College, City University of New York, emphasizes need for more fossils to determine whether the kneecap belonged to a young Danuvius that had not yet reached full size.

Discoveries at Hammerschmiede highlight how much remains unknown about evolution of great apes, including our own lineage, during Miocene in Europe. As researchers continue to uncover more fossils, they hope to piece together complex puzzle of primate evolution during this important period.

- Scientists make first-of-its-kind discovery on Mars – miles below planet’s surface

- Earthquakes added to Pompeii’s death toll

- Best Android apps for science lovers

FAQ: Europe’s Role in Ape Evolution Expanded by Fossil Discoveries

Why are fossils found at Hammerschmiede important?

Fossils are important because they show that two different species of ancient great apes, Danuvius and Buronius, lived together in Europe millions of years ago. This is first time that researchers have found different great apes coexisting outside of Africa.

Who were Danuvius and Buronius?

Danuvius was larger great ape known for possibly being oldest upright walker. Buronius is smaller great ape recently discovered at the same site weighing only about 10 kilograms.

How were Danuvius and Buronius different?

Danuvius was about twice size of Buronius and had strong teeth for eating tougher foods like nuts and small animals. Buronius was much smaller and likely ate softer foods like leaves and fruits while spending most of its time climbing trees.

What does this discovery tell us about ancient Europe?

This discovery suggests that ancient Europe had rich and diverse environment where different species of great apes could live together each with its own way of surviving.

Why is there uncertainty about Buronius?

There’s still some uncertainty because only three Buronius fossils have been found so far. Some scientists think these fossils might actually belong to young Danuvius individuals instead of a separate species. More fossils and research are needed to be sure.

How does this discovery help us understand primate evolution?

This discovery shows that Europe played key role in evolution of great apes and reminds us that there’s still much to learn about how our ancestors evolved during this critical time period.